HMRC get heavy handed and send out some nasty letters

For those who don’t know Taxation is a magazine targeted at tax advisers and accountants so the language contains jargon. But having said that this was one of the more accessible pieces and it covers very important changes in the way HMRC goes after people like you in tax investigations.

Will the Revenue’s behavioural insight techniques whip taxpayers into shape?

KEY POINTS:

[fancy_list style=”bullet_list” variation=”red”]- HMRC are using behavioural insight techniques.

- Object is to discourage some tax planning.

- Specific letters are misleading, exaggerated and confusing.

- Too heavy-handed to be called a “nudge”.

- How “effective” will these techniques be?

The tax planning (or tax avoidance if that is your preference) debate rumbles on with the familiar mix of bluster, ignorance and confusion. HMRC’s position is pretty clear: they do not like some planning. HMRC have the usual tools of enquiry, litigation and legislation but, as has recently become apparent, new techniques are emerging.

In HMRC’s evidence to the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) on 4 December 2012, it was said. “HMRC has established a pilot project to evaluate the use of behaviour change techniques to ‘nudge’ users by writing to them to encourage withdrawal from avoidance schemes.”

Nothing was said about how much this will cost, nor how the effectiveness of this technique will be measured, but no doubt the PAC will in due course ask whether the money has been well spent.

According to the online Oxford Dictionaries, the verb nudge means “coax or gently encourage (someone) to do something”, while the noun is defined as “a light touch or push”.

I have come across four different types of letter in connection with employee benefit trusts (EBTs) which, although they do not appear to be the letters referred to by HMRC in the PAC evidence, seem to be part of a similar project. They go well beyond what could realistically be viewed as a “nudge”.

How did HMRC get into this position? Was it like this?

The plan

Guru: Guys, Great to be working with you. You are the choice architects of our project. What noises do these people … whaddya call them?

Inspector Old: Well, we are meant to call them customers, but we all still say taxpayers.

Guru: “Customer” is just perfect. Right, what noises do these customers not like to hear?

Officer Young: They don’t want to be told they will pay more tax, or that HMRC are going to win, or that they may face litigation and that it could be expensive. Company directors don’t want to be told we’ll come after them for company tax. We could even mention penalties or naming and shaming.

Guru: Great stuff! We’ll get all that in.

Old: But we have lost some cases in litigation on EBTs. Plus there are quite good defences when we try to attach corporate or employer liabilities to directors and we have no evidence at all that penalties could be due.

Guru: We’ll emphasise the positive from our point of view. Now, can we offer them something sweet?

Young: Well, we really want them to settle EBTs on our terms. Could we say that lots of other people are settling?

Old: Except that they aren’t.

Guru: No worries. We won’t tell untruths. It’s all about touching an elemental level – so we just give impressions. It’s all in the book. You guys have copies – right?

Young: Of course! It was brilliant. We have to get directly to the taxp… uh customer though. We don’t want their accountants filtering the message.

Old: Lots of them will have accountants with 64-8s in place. It’s a form that authorises HMRC to deal with agents. Non-statutory correspondence is governed by the terms in Your Charter and we are required to write to the accountant who would then pass it on to his client.

Guru: No, no, no. We can’t have that. Set it up so that all the letters go direct to the customer. I suppose we can send some copies to the advisers or just tell them to take advice.

Young: No problem.

Guru: We need some emotion.

Young: How about a hint that they’re being good citizens?

Guru: Good idea. We’ll get that in one of the letters. Now, how about sympathy and understanding?

Old and Young: Huh?

Guru: Yeah, show the customers you care. Maybe they didn’t know what they were getting into. All they need is someone to talk to.

Old: This’ll never work. We’ll just waste time and money.

Guru: No, no, no. You may be status quo biased. The beauty of this is it is so cheap. We’ll have different types with the same basic message: some empathetic, some to induce guilt, and some to scare. These customers will be eating out of your hands in a few weeks.

Young: We’re on it.

The letters

Well, maybe. Of course, there can be no objection in principle to HMRC using resources in this way (although the PAC might ask about the costs and outcomes or some enterprising freedom of information campaigner will seek that information).

HMRC have been tasked with increasing the tax take and, if they think that letters of this type will achieve their goals, doubtless they will use them. But where HMRC take a moralistic tone on tax planning, it is surely necessary to ensure that their own behaviour is above reproach, quite aside from the high standards we expect from a great department of state.

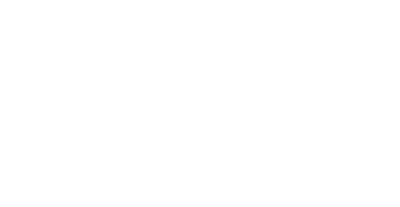

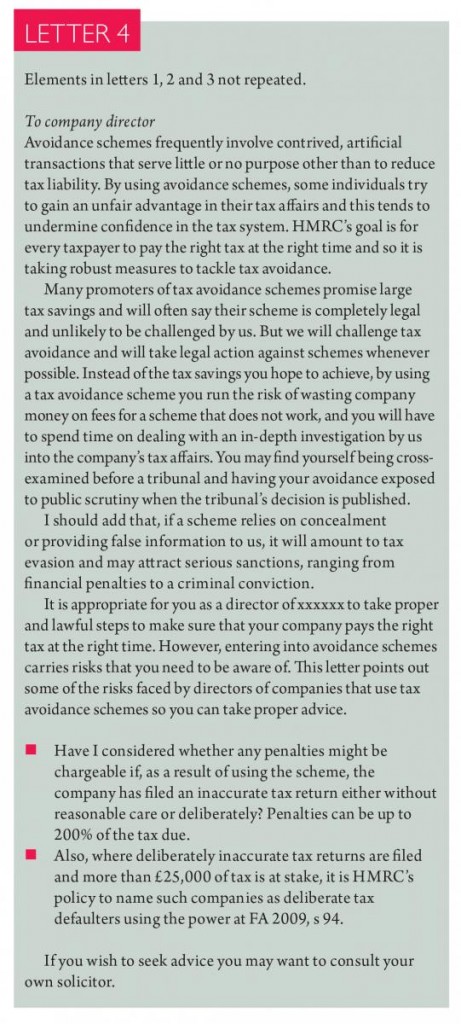

Sadly, in my view, some of the behavioural insight letters are open to serious criticism. Extracts from the four types of letter mentioned in the introduction are reproduced in Letter 1, Letter 2, Letter 3 and Letter 4 (which can be found throughout this article; click on the images to enlarge).

Although the letters are about companies that did the planning, many were sent direct to individuals, bypassing any corporate or personal agent who may have been authorised to receive HMRC correspondence.

In some cases, copies were sent to the companies’ agents, in others it was recommended that tax advisers or lawyers be consulted. Indeed, in some cases, HMRC officers are following up their letters with calls direct to the company asking whether settlement is to be pursued.

Yet HMRC’s charter says they will respect the representative’s right to act for the taxpayer and deal with them appropriately. Except, it appears, when it doesn’t suit HMRC.

If the policy on working with agents is that forms 64-8 and other authorities will be ignored at HMRC’s convenience, then I suggest that this should be made clear on HMRC’s website, on the 64-8 notes, and in Your Charter.

The opening language is assertive, even confrontational in tone, which seems at odds with the “nudge” philosophy.

There is a reference to arguments put forward “specifically in the course of the enquiry into your company’s returns and computations”. Many EBTs have been administered under a representative sample arrangement and, consequently, only a sample received detailed information requests from HMRC.

In my experience, even those in the sample have not received detailed HMRC arguments. A client reading this paragraph might assume, probably incorrectly, that specific arguments had been made in his case about which his advisers had not told him.

A misleading impression

The main problem with Letter 1, direct to the taxpayer, is that it gives an incomplete impression of the state of the arguments on EBTs.

These letters were all written after the decision of the First-tier Tribunal in Murray Group Holdings and Others v HMRC was published.

While the “remuneration trust” in that case is not necessarily on all fours with most EBTs, the majority of the judges that heard Rangers clearly rejected the HMRC technical arguments.

Doubtless HMRC were very disappointed with that decision and, indeed, have appealed it.

But in a letter to a taxpayer, who could not be expected to be expert in tax, HMRC attempted to cajole the recipient into making a large payment to the government.

The letter made no reference to the Rangers case at all which, I believe, was misleading. One might say that this gave a “contrived” impression of the state of the debate.

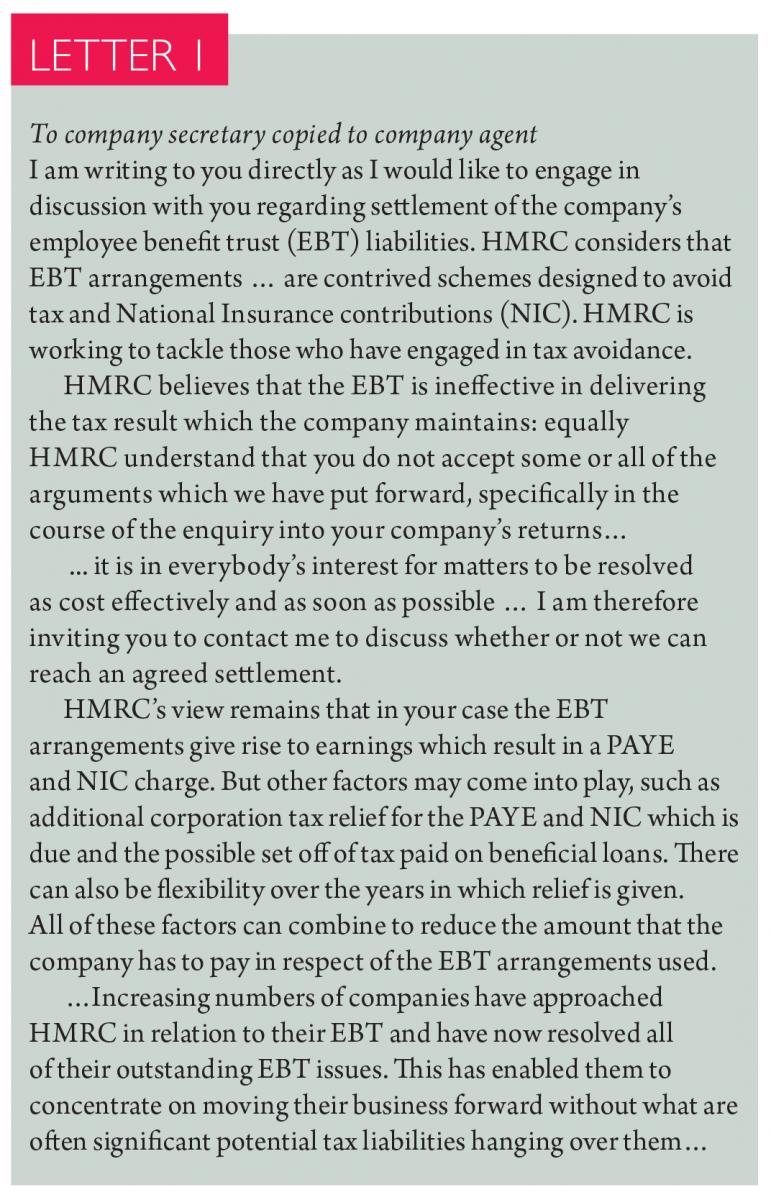

Letter 2 tries to be more empathetic and does take a sensible commercial approach. HMRC’s confidence that the courts may uphold its view may, of course, be proved correct.

But it was again misleading not to draw its lack of success in Dextra, Sempra and Rangers to an unrepresented taxpayer’s attention.

Some advisers will also have been annoyed at the suggestion that advisers may not have accurately informed clients of all the terms of the HMRC “settlement opportunity”.

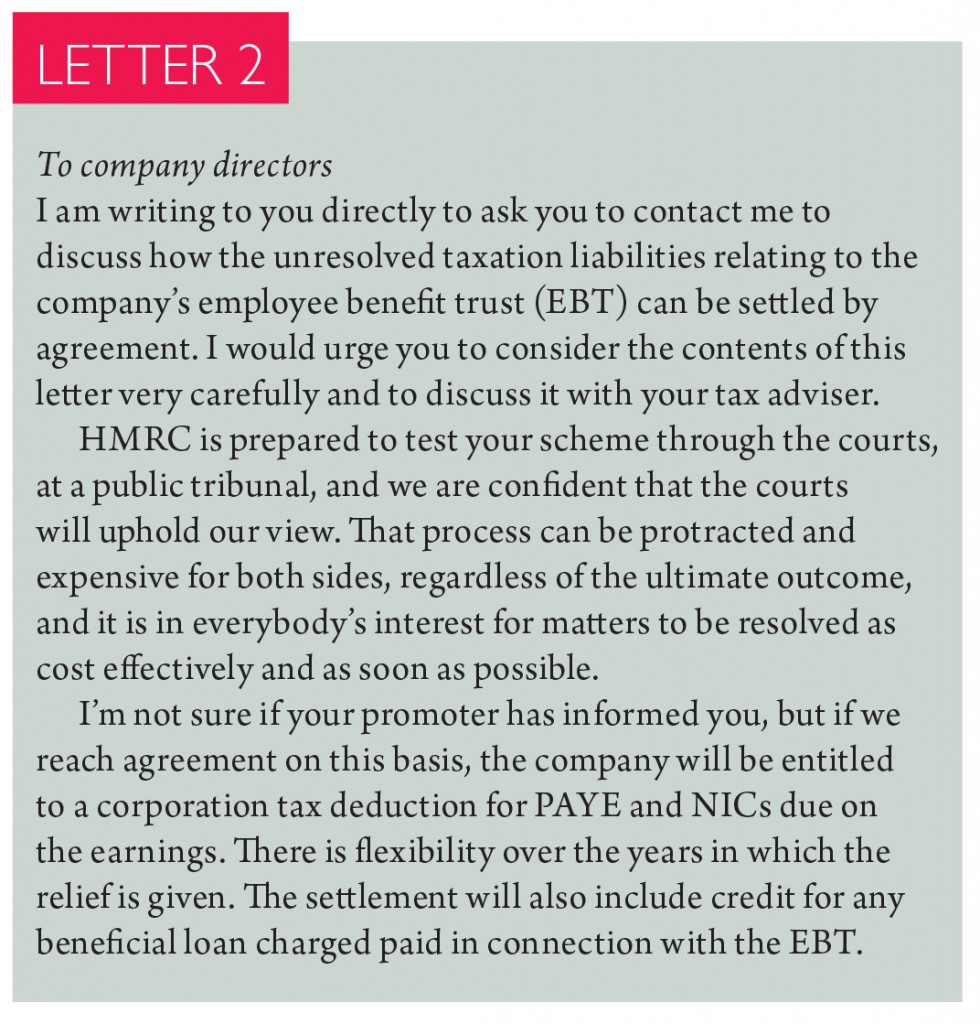

The purpose of the Letter 3 version seems to be to shake the director’s confidence in limited liability.

What is said is not inaccurate; however, it does not seem any effort was made to establish whether the companies that were the subjects of these letters might be unable to meet their tax obligations if litigation ultimately showed that PAYE and NIC were due.

Lacking that specific context, the impression given is that this letter was to try to unsettle directors.

Furthermore, even if action was contemplated against directors under the insolvency rules because a company could not pay a tax debt, those who provided this wording must have known that there is a defence where there is reasonable reliance on expert advice.

HMRC will be aware that the EBT clients of EDF Tax Ltd (EDF) have relied on expert advice throughout and it is likely that most other EBT users will have too.

I suggest that it was partial and misleading to make those assertions without explaining all the defences available. The absence of a complete picture suggests that HMRC’s object was merely to undermine directors’ confidence and so encourage settlement discussions with the officer.

Menaces and moralising

Letter 4 is a lot more menacing and shares many of the flaws of the others. The talk of “unfair advantage”, “undermines confidence in the tax system”, and “proper and lawful steps to make sure that your company pays the right tax at the right time” will meet with approval in some quarters, but to my mind it introduces a wholly unnecessary moralising tone which privileges HMRC’s view of what the law should say.

I am aware that some “promoters … promise large tax savings, and will often say their scheme is completely legal and unlikely to be challenged by us”. But surely before making such an allegation HMRC should at least check that it would be appropriate in that client’s situation.

They are aware that it is not appropriate in EDF’s cases; despite this, they intend to send a similar letter to EDF’s and others’ clients that have used post-disguised remuneration planning.

The fact is that most professional advisers will outline the risks attached to tax planning and will inform clients that HMRC will make enquiries, so language such as this is inaccurate and unhelpful.

Have HMRC any reason to believe that if these arrangements were litigated that the companies whose directors received this letter would be a lead case and that the directors would be asked to give evidence?

HMRC is well aware that it does not have the resources to litigate each case separately and that it is very unlikely that any more than one client would be a test case.

So, again, the purpose seems to be more to frighten the director than to give accurate information. Is that an appropriate way for HMRC to behave?

There then follow the remarks from the department about the unpleasant consequences if errors, especially deliberate errors, are made.

It has occasionally happened that so called tax planning was nothing but tax dishonesty in disguise.

But did HMRC have any reason to believe that the companies to which letters have been sent had taken such a foolish and dangerous step?

If they did, they would doubtless have considered a criminal investigation.

It seems much more likely HMRC were merely trying to scare the directors. The same can be said about the references to the 200% penalty and naming and shaming.

Penalties can indeed be up to 200% of the tax due, as provided for by FA 2010, Sch 10, which entered into force on 6 April 2011. However, this applies where there is a deliberate and concealed inaccuracy in “category 3”.

It is unlikely that EBT or similar planning would have the necessary connection with category 3 territories (see the list at HMRC’s Compliance Handbook at paragraph CH82484) and certainly the EBTs with which I am familiar do not. It is hard to see the customer service point in mentioning this new and highly restricted penalty.

If the intention was merely to unsettle and disturb the reader then this sort of exaggeration is misleading and wholly undermines the emphasis earlier in the letter about having confidence in the tax system and, indeed, its administrator.

Similar points can be made about the reference to naming and shaming (FA 2009, s 94), which depends on deliberate errors in a return after 1 April 2010.

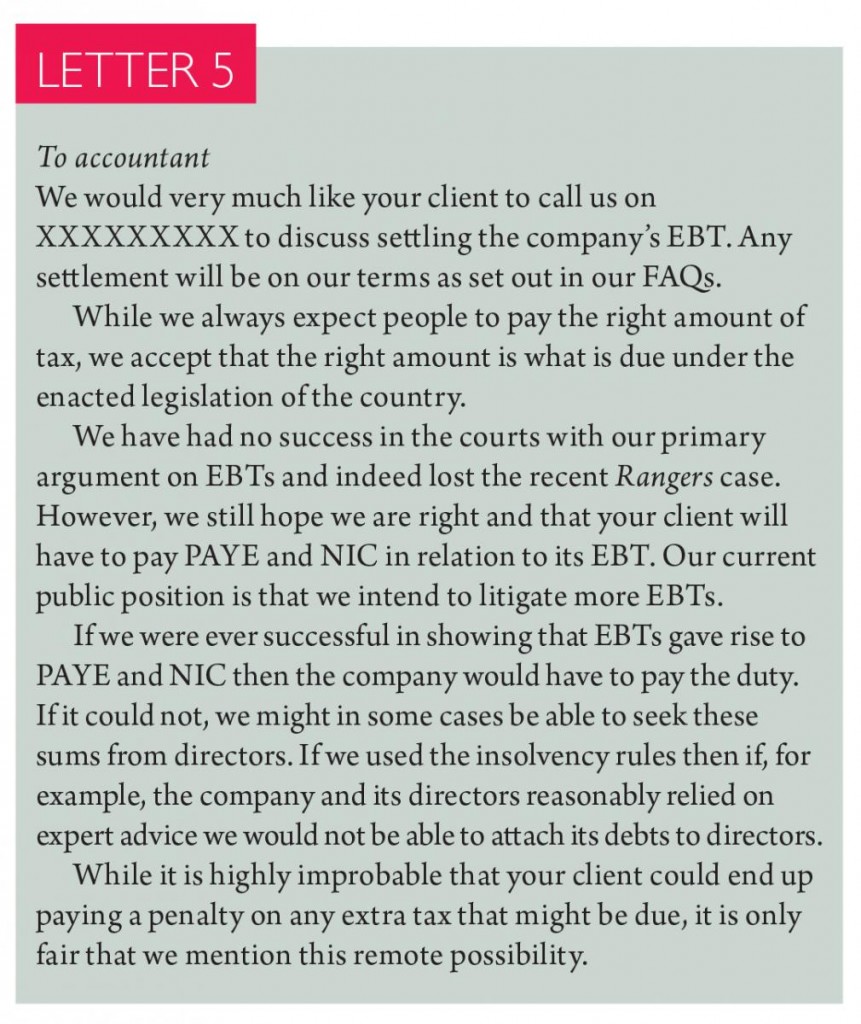

An accurate letter

If HMRC had concentrated less on drama and impact and focused more on accuracy and the meaning of “nudge”, might such a letter have looked like that in Letter 5?

I believe my draft better fits the description of a “nudge” than the HMRC versions, but it is not very exciting and would doubtless have been discarded.

Similar comments can be made about the draft letter which was included in the evidence to the PAC and which is mentioned above.

Although this is not about EBTs, the same principles seem to apply.

This draft says the recipient “needs” to call HMRC.

An unrepresented taxpayer may well conclude they had an obligation to call or even meet with HMRC.

This may be good marketing and, doubtless, what HMRC would like; but this sort of wording is misleading.

It would have been more straightforward to say, “We need you to call HMRC, but you are under no obligation to do so.”

Although the draft produced for the PAC says: “If we find that the scheme does not work as intended…”, I understand that the version sent also said: “Our view of this scheme is that it does not work as intended.” The mixture of ambiguity and certainty is confusing.

And then there is a threat about penalties which, so it is said, could be greater if the taxpayer does not get in touch.

As HMRC accept, for example, in the Enquiry Manual at EIM1861, that they have no power to compel attendance at a meeting and therefore by implication cannot oblige taxpayers to speak on the telephone either, it is hard to see how this threat is justified.

[fancy_box title=”Conclusion”] It will be interesting to know what impact these letters have and whether one of them turns out to be more effective, from HMRC’s perspective, than the others.In principle, advisers can have no objection to letters of this general type. But, if this is tried again, HMRC should concentrate on accuracy and follow its own guidelines rather than try to grab attention with exaggeration and misleading assertions.

[/fancy_box]